A celebrated architect’s Wellfleet house needs rescuing

Real Estate

Marcel Breuer’s summer home in Wellfleet, Mass., a time capsule of architectural history hidden in the wilderness, has fallen into disrepair.

WELLFLEET, Mass. — Deep in the woods of Wellfleet, on Cape Cod, down winding and rutted dirt roads, a summer home built in 1949 by modernist architect Marcel Breuer sits perched on stilts. Its cantilevered porch, where friends and family would spend much of their time, once had a clear view across three connected kettle ponds, but saplings that dotted the hillside today tower above the house, blocking sightlines.

The four-bedroom structure, now owned by the architect’s son, Tamas Breuer, is considered the most significant modernist house on the Cape and was one of the first completed examples of Breuer’s “Long House” design, a simple construction that could be assembled using local materials. It has been left unchanged for decades, a time capsule of architectural history hidden in the wilderness.

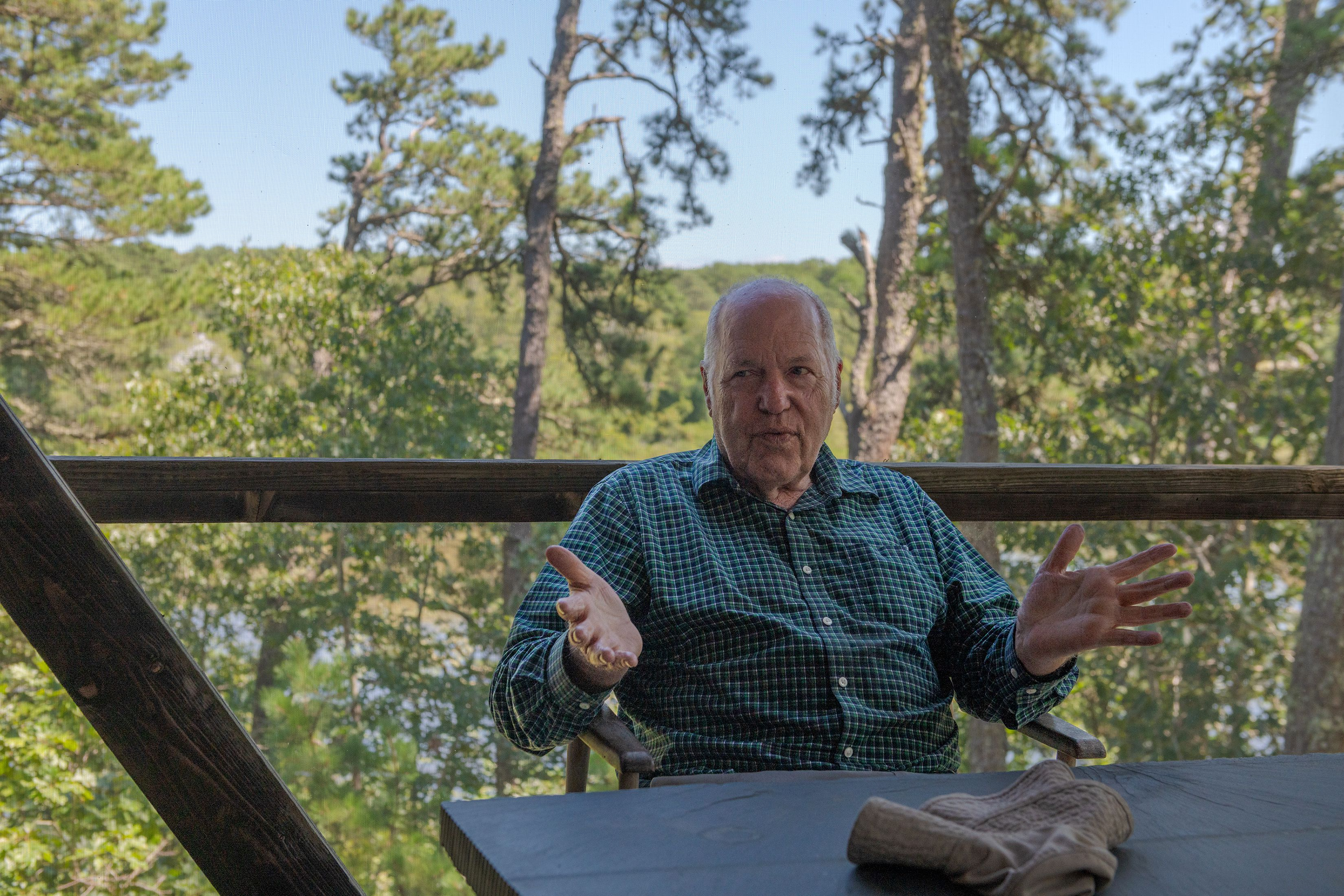

But the damp New England weather has taken its toll on the cabinlike building, especially on the north side, where moss and lichen have rotted some of the white cedar cladding and porch rails. A leak in the roof has damaged the birch plywood ceilings in the main living room. And Tamas Breuer, who is 80 and likes his privacy — he declined to be interviewed but was welcoming during a tour of the house last week — spends just a month here each year and has wanted to sell the property.

The Cape Cod Modern House Trust is under contract to buy the house, and is looking to raise $1.4 million to preserve the building and its contents, including an art collection with works by friends of Marcel Breuer’s, including Alexander Calder, Paul Klee, Saul Steinberg and Josef Albers.

“In a year, if we can’t raise the money, the house could be on the market and it could be demolished,” said Peter McMahon, an architect and the founding director of the trust, which documents and restores Modernist properties on the Outer Cape.

Although most of the art and books have been removed from the house for cataloging and conservation, many personal items remain, including a woman’s yellow robe and handbags hanging on a bedroom closet door, a vintage tabletop TV set with antenna and an upright piano that Marcel Breuer’s wife, Connie (Constance Crocker Leighton), would play at parties, and that Tamas Breuer keeps in tune.

The house was built on land Marcel Breuer bought with the aim of creating an artistic community, and he soon tempted other Bauhaus friends to join him on the Cape, including painter and designer Gyorgy Kepes, for whom he built an identical home on Long Pond. Architect Serge Chermayeff lived across the road, where Breuer’s mentor Walter Gropius would stay, while landscape architect Charles Jencks had a home and a studio nearby.

“Breuer wanted to have an intellectual enclave with those who shared his aesthetic points of view,” said James Crump, who directed the 2021 documentary “Breuer’s Bohemia,” interviewing many of the group’s surviving family members and friends. They tell of the summers spent in Wellfleet, canoeing across the ponds, sharing meals and socializing at one another’s homes, swimming in the adjacent Atlantic waters — often naked.

The tradition of spending carefree summers enjoying nature is “a transposition of something that was part of the artistic and lifestyle culture of the Bauhaus,” said Barry Bergdoll, a Breuer expert who teaches art and architectural history at Columbia University.

Marta Kuzma, a curator and a former dean of the Yale School of Art, who visited the Breuer house in July, described finding a spirit of experimentalism in every room, from furniture built — and endlessly rearranged — by Breuer using cinder blocks to a necklace made from a found circuit chip. “That sense of whimsy you don’t usually get when you are looking at the modernist period,” Kuzma said. “On Cape Cod, they were able to just have fun.”

The Wellfleet house was so important to Breuer that, after his death in 1981, his ashes were buried among the pine trees in the yard, under a stone cut from a sculpture by Japanese artist Masayuki Nagare. An enigmatic inscription reads: “Here Marcel Breuer broke his knee entirely of his own stupidity.” His wife’s remains are also buried there (she died in 2002), along with those of her sister Elizabeth Leighton and her husband, artist Robert Jay Wolff.

The trust maintains four other homes in the area, hosting artist residencies in them and arranging public tours. Its operating revenue comes from renting the homes out to donors. These properties are leased from the Cape Cod National Seashore, so the Breuer home would be its first acquisition. It aims to use it for an annual fellowship, housing visiting students and scholars who would be involved in archiving and preservation efforts.

The importance of saving the Breuer property is not lost on local officials. “If purchased by the trust, the (Breuer) building will be safeguarded from demolition, which would be highly likely if the property is sold on the open market,” said Lilli-Ann Green, delegate for Wellfleet, during a Barnstable County assembly meeting on Aug. 16, when a resolution was passed in support of the restoration project. Just last year, another home built by Breuer in Lawrence, Long Island, New York, was torn down, upsetting preservationists, and one by architect George Nelson in the Hamptons, which was bought for $60 million in 2021, was bulldozed this year.

Breuer’s house in Wellfleet sits on a hill overlooking 4.2 acres of undeveloped waterfront, and the town assessor has valued the land alone as worth $1.2 million. “It’s on a huge piece of property,” Brian O’Malley, the delegate for Provincetown, said during the assembly meeting. “If it’s sold, the impact of development is going to drastically change that entire part of Wellfleet (and) Truro ponds and woods. It would be a great, great loss to the Outer Cape, beyond the house itself.”

The surrounding forest is overgrown, and there will need to be some work done to make the site accessible, leveling the driveway, and removing dead pine trees that could fall on the house. But the landscape will most likely be left wild, drawing on Bauhaus ideals of finding inspiration from nature.

Henry David Thoreau, after all, stayed in a Wellfleet oysterman’s house across Williams Pond in 1850, during his travels through Cape Cod. And the Breuer property’s southern border is on the headwaters of the Herring River, which is currently the focus of a $60 million environmental restoration project led by the National Park Service to return tidal flow and natural salt marshes to the area, lost over the decades because of rising sea levels.

The land and the historical building are not the only things the trust will be acquiring, since the house contains Breuer’s personal art collection and more than 200 books on architecture and design, many of them inscribed to him. An atlas by Bauhaus graphic designer Herbert Bayer, for example, includes a note that reads, in German: “For Lajko and Connie Breuer, in old friendship,” using Breuer’s nickname among friends.

“A lot of the art was exchanged when (the family) were all still there,” McMahon said, and much of it has been untouched since then. “An Albers woodblock was stuck in an envelope and mailed to [Breuer] — and it was still in the envelope.”

Breuer added a studio and a small apartment with a darkroom to the house in the 1960s, to encourage Tamas Breuer’s interest in photography. “There’s hundreds and hundreds of rolls of film,” McMahon said, documenting the home from the 1960s to the ’80s, as well as everyone who visited. Tamas is helping to put names to the faces that appear on large contact sheets printed from the scanned negatives. “It’s like somebody was making a documentary film for 30 years, with these older Bauhaus people visiting and all the local luminaries,” McMahon said, “the parties, and bonfires and openings.”

If the house were sold on the open market, not only could the architecture be lost and the art scattered through a dealer or auction house, but the new owner could decide to scrap much of this documentation. “It would really be a shame,” McMahon said. “It would disappear.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Originally posted 2023-08-24 14:05:54.