Conspiracy theories about FEMA’s Oct. 4 emergency alert test spread online

Technology

One popular video shows a woman claiming the test will somehow switch on technology that has been introduced into people’s bodies.

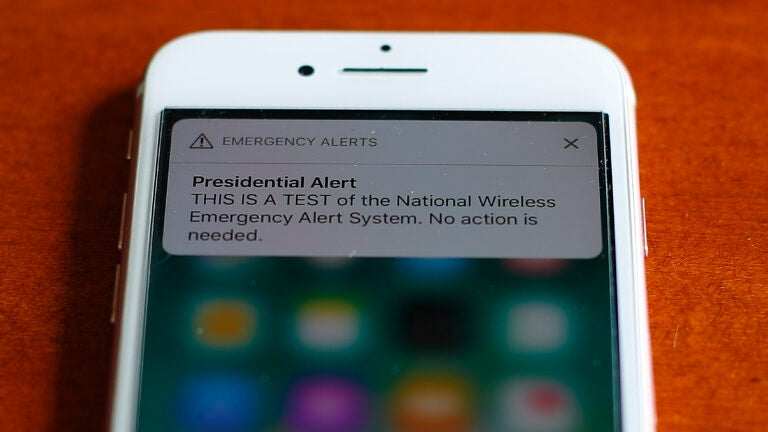

Claim: An emergency broadcast system test on Oct. 4 will send a signal to cell phones nationwide in order to activate nanoparticles such as graphene oxide that have been introduced into people’s bodies.

AP’s Assessment: False. Next month’s test of the nationwide Emergency Alert System uses the same familiar audio tone that’s been in use since the 1960s to broadcast warnings across the country. A spokesperson for the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which is overseeing the test, also said there are no known adverse health effects from the signal. The claims revive long-debunked conspiracy theories about the contents of the COVID-19 vaccine.

The facts: Social media users are raising dire warnings about upcoming tests of the national emergency warning system.

Many are imploring their followers to shut off their cellphones on the day of the test because they believe it’s part of a broader conspiracy to exert control over the population.

One popular video shows a woman claiming the test will somehow switch on technology that has been introduced into people’s bodies.

“The emergency broadcasting system under FEMA is going to be activated,” the woman explains, speaking directly into the camera. “It’s not a test. It’s going to be sending these high frequency signals into cell phones, radios, TVs. The intention of activating nanoparticles, including graphene oxide.”

In another widely shared video, a man issues a similar warning, adding that graphene oxide and other nanoparticles have been inserted into billions of human beings around the world “through obvious mediums.”

“Everyone will be affected, regardless of status,” he adds in the video, which was widely shared on X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, along with the hashtag “CovidVaccine.”

But while FEMA is conducting a routine test of its emergency warning system next month, there is no truth to the claim that it will emit a wireless signal that will somehow activate graphene oxide or nanoparticles in the body.

Stanley Perlman, professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said the claims appear to be referring to old myths about the contents of COVID vaccines.

These baseless conspiracy theories claim — without evidence — that the vaccines contain various materials, such as graphene oxide or other nanoparticles, that can interact with wireless communications technology. They claim that the materials, when activated, can allow governments to control and monitor people.

But graphene oxide — a material made by oxidizing graphite — isn’t an ingredient in the COVID vaccine, notes Matthew Laurens, a pediatric infectious disease specialist with the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

“Graphene oxide is not in the mRNA-based vaccines for COVID-19 manufactured by Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna,” he wrote in an email Monday. “Graphene oxide was used to study vaccine structure only, and is not part of the vaccine formulation.”

Regardless, the notion that graphene oxide can be “activated” in this way is “nonsense,” wrote Julia Greer, a materials science professor at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena who has used graphene oxide in her research, in an email Monday.

“You can’t ‘activate’ graphene oxide,” she wrote. “What does that even mean?”

The actual nanoparticles in the vaccines, meanwhile, are lipids, or fats, that are generally used as a coating material. They’re sometimes described as “programmable” because they can be modified and adjusted, depending on the need, experts have said. It does not mean they can be programmed to interact with wireless networks.

There’s also nothing nefarious about the routine test FEMA and the Federal Communications Commission are conducting next month.

Such tests have been happening with regularity for years now without any reports of adverse health effects from the system signals, said Jeremy Edwards, FEMA’s spokesperson.

“The sole purpose of the test is to ensure that the systems continue to be an effective means of warning the public about emergencies, particularly those on the national level,” he wrote in an email this week.

The two nationwide systems — the Emergency Alert System, or EAS, and Wireless Emergency Alerts, or WEA — are “critical tools” that save lives and allow people to protect property when natural disasters, acts of terrorism and other threats to public safety strike, Edwards added.

Next month’s test is slated to begin on Oct. 4 at around 2:20 p.m. eastern time, but could be postponed to Oct. 11 if there’s severe weather or other significant events, according to FEMA.

The process involves two parts: a 30-minute signal sent to radios and televisions as part of EAS, and a similar one sent to all consumer cell phones as part of the WEA system.

According to FEMA, the message to be broadcast will state: “This is a nationwide test of the Emergency Alert System, issued by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, covering the United States from 14:20 to 14:50 hours ET. This is only a test. No action is required by the public.”

Federal law requires the systems be tested at least once every three years. The last nationwide test was Aug. 11, 2021.

Edwards said the audio signal used for the tests utilizes the same combination of tones familiar to Americans since 1963, when President John F. Kennedy established the original Emergency Broadcast System through an executive order.

It’s also the same tone as those sent by more than 1,700 local, state, territorial and tribal authorities that send similar alerts for more localized emergencies.

This is part of AP’s effort to address widely shared misinformation, including work with outside companies and organizations to add factual context to misleading content that is circulating online. Learn more about fact-checking at AP.

Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com