Politics

An indictment in the Georgia election conspiracy case marked perhaps the lowest point in the career of Rudolph W. Giuliani, who had staked his legacy on blind allegiance to the Trump administration.

Early in the scrum of the 2016 presidential campaign, political strategist Rick Wilson bumped into an old boss and strongly advised him not to cast his lot with Donald Trump. No good would come of it.

“Even if he wins, he’s going to destroy you,” Wilson remembered telling Rudy Giuliani. “This guy’s going to humiliate you.”

Wilson recalled being dismissed as a provincial Floridian unable to understand the bond between two New Yorkers — outer-borough strivers who walked the Manhattan streets with proprietary airs and were now within grasp of once-unimaginable power.

“He’s going to take care of me,” Wilson said Giuliani would tell those around him. A Cabinet post, probably. Maybe secretary of state.

-

Trump and 18 allies charged in Georgia election meddling as former president faces 4th criminal case

Never happened. Instead, Giuliani became Trump’s secretary of aggression and blind allegiance: his attack dog, legal adviser, unindicted co-conspirator — and now, co-defendant in a criminal conspiracy case.

The two friends from New York, along with 17 others, were indicted Monday in Georgia in a broad racketeering case centered on the sobering charge that they illegally plotted to overturn the 2020 presidential election in favor of its loser, Trump. Adding to the ignominy for Giuliani, 79, is that he was once an innovative prosecutor who specialized in federal racketeering cases.

“I think it’s going to be scary for him,” said Wilson, a former Republican who worked as an adviser to Giuliani a quarter-century ago and is a leading conservative critic of Trump. “The justice system is ringing his bell and calling him to account.”

On Tuesday, Giuliani responded to his indictment by calling it “just the next chapter in a book of lies with the purpose of framing President Donald Trump and anyone willing to take on the ruling regime.” The Georgia case, he added in his prepared statement, “is an affront to American democracy and does permanent, irrevocable harm to our justice system.”

On Monday night, as the grand jury in Fulton County, Georgia, prepared to hand up the 41-count indictment, Giuliani could be seen on his nightly livestream show, “America’s Mayor Live,” watching a broadcast of the goings-on at the Atlanta courthouse, making sardonic comments and trying to appear unfazed.

“He’s the consummate happy warrior,” Ted Goodman, Giuliani’s political adviser, maintained.

Still, the criminal indictment of Giuliani, his first, marks the lowest point so far in his yearslong reputational tumble. Once heralded as a fearless lawman, game-changing New York City mayor and 9/11 hero, he is now defined by a subservience to the 45th president that sometimes veered into buffoonery.

Daniel C. Richman, a former federal prosecutor who worked under Giuliani when he was the U.S. attorney in Manhattan, is among a legion of former colleagues who struggle to reconcile the Rudys of then and now.

“I found him to be an inspiring leader,” recalled Richman, now a professor at Columbia Law School. “He was very focused on the law, committed to what the right thing was — and doing it.”

He said that while Giuliani’s tenure as mayor, from 1994 through 2001, had its highs and lows, “he rose to the occasion on Sept. 11,” reassuring New Yorkers after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan.

Now?

“In his sad commitment to be relevant, he has thrown himself in with a crew where facts and the law are either irrelevant or there to be twisted,” Richman said. “It’s the thirst for relevance. The thirst to be in the mix.”

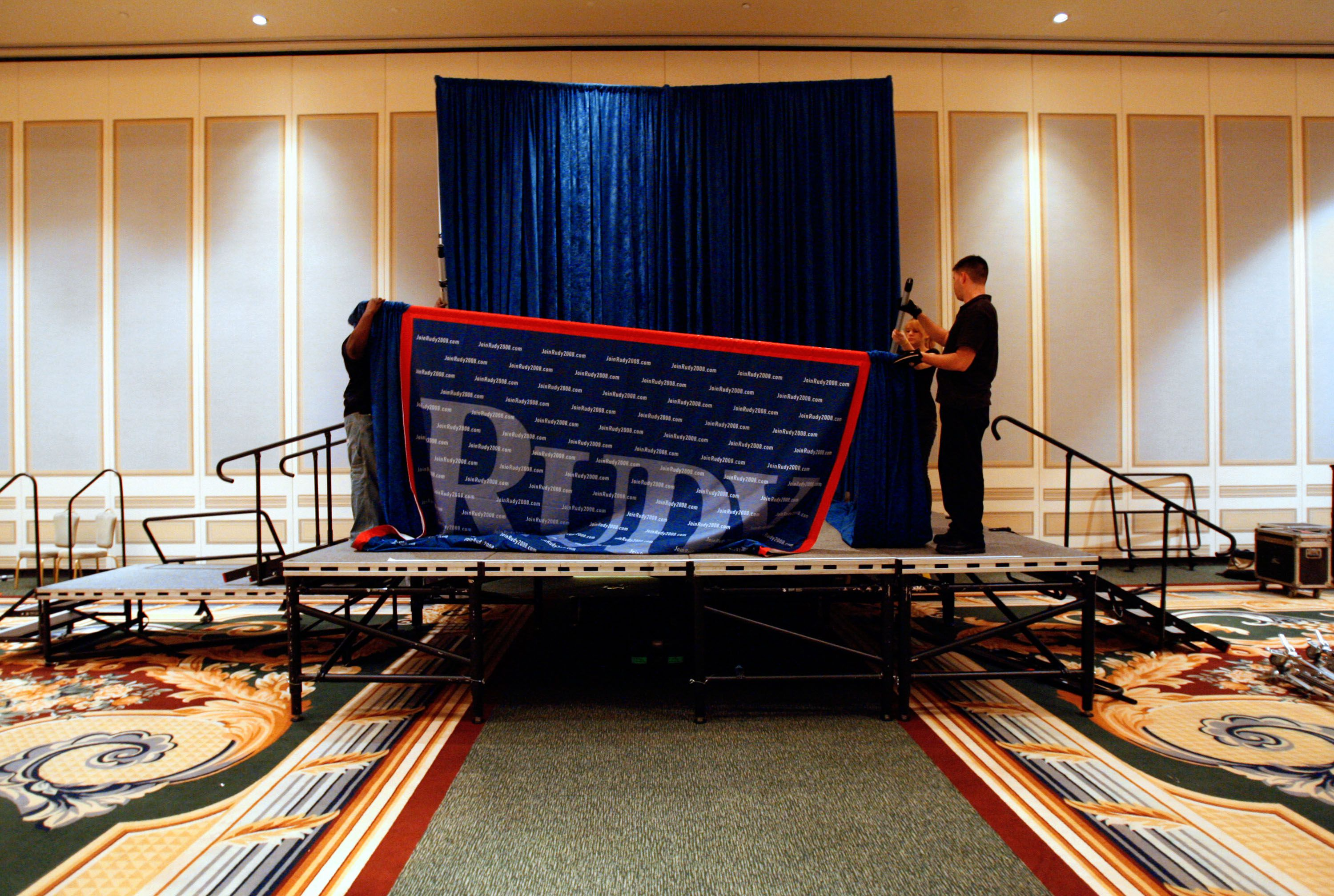

Less than a decade after leaving City Hall amid international acclaim — he was Time magazine’s 2001 Person of the Year — Giuliani was a political also-ran. His inept and costly bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 2008 left the campaign about $3.6 million in debt and the candidate, as he later admitted, feeling intimations of irrelevance.

This was an especially dark period for Giuliani, according to journalist Andrew Kirtzman, whose 2022 book, “Giuliani: The Rise and Tragic Fall of America’s Mayor,” describes the former mayor as depressed, self-pitying and drinking to excess.

But Trump came to his aid, Kirtzman wrote, providing Giuliani and his then-wife, Judith Nathan, with several weeks of refuge in a secluded cottage at his Florida resort, Mar-a-Lago.

Giuliani was able to return the favor, as well as return to the spotlight, several years later. During the 2016 presidential election season, he not only endorsed Trump — against the advice of the likes of Wilson — he became a defender so ferocious that some wondered about his mental well-being.

But when Trump became embroiled in a federal investigation, led by special counsel Robert Mueller, into possible Russian interference in the 2016 election, Giuliani replaced the president’s personal lawyer and, once again, emerged as his fiercest defender. Dealing with a divorce from his third wife and no longer holding a well-paying position at a prominent law firm, he thrust himself ever deeper into the chaotic Trumpian sphere.

Before long he was working to further the president’s political ambitions by trying to persuade top Ukrainian officials to investigate and damage Trump’s likely rival for the 2020 election, Joe Biden. His immersion into Ukrainian matters was so deep that federal prosecutors in Manhattan opened a criminal investigation into Giuliani that was eventually closed, but not before a search warrant had been executed at his Upper East Side apartment.

All the while, Giuliani’s pattern of curious legal interpretations, provocative statements and odd behavior kept him in an often unflattering spotlight.

One example: He was duped into appearing in the Sacha Baron Cohen satire “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm,” in which the president’s personal lawyer is seen putting his hands down his pants while reclining on the bed of a young actress posing as a reporter. He later said he was tucking in his shirt after removing a microphone.

All mere prologue.

On election night 2020, with Trump’s chances fading by the hour, the president nevertheless declared victory, while also alleging electoral fraud, egged on by a conspiracy-focused Giuliani. Later, in testifying before the congressional commission investigating the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, Trump aides described Giuliani as having been highly intoxicated that night, a description he has rejected.

Several days later, on Nov. 12, Trump’s election lawyers advised the president that they could find no evidence of election fraud, notwithstanding what he had been asserting publicly. But Giuliani prevailed again, this time by sharing the specious theory that Dominion voting machines had converted thousands of Trump votes into Biden votes, and by encouraging the president to file a lawsuit in Georgia.

Giuliani’s actions from this point on are detailed in Monday night’s indictment, which echoes the federal indictment filed this month, in which Trump was charged with plotting to overturn the results of the 2020 election and Giuliani appears as unindicted “Co-Conspirator 1.”

The most recent indictment describes, step by frantic step, how Giuliani possessed a bullheaded determination to prove against all evidence that the election had been stolen, leading a supposedly “elite” team of lawyers that filed dozens of legal challenges across the country and hitting the road with outlandish theories.

Each step, the indictment said, constituted “an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy” — legal terminology no doubt acutely familiar to the former federal prosecutor.

Two of his news conferences approached political farce. The first came outside the Four Seasons Total Landscaping company in Philadelphia, near a crematorium and a sex shop, where he made easily refuted allegations about ballots cast by the dead. The second is remembered for a dark liquid, possibly hair dye, trickling down Giuliani’s face as he cast further doubt on the election results.

A central stop on his fraudulent-election tour was Georgia, where an audit of ballots had already confirmed that Trump had lost the state. Still, Giuliani appeared at state legislative hearings to make a series of false, even outrageous, claims. Among them:

That election workers had suitcases filled with questionable ballots that they would count after Republican poll watchers left; that 10,315 dead people had voted; that some ballots had been counted five times; and that two Black election workers, Ruby Freeman and her daughter, Wandrea Moss, who goes by Shaye, had been “quite obviously surreptitiously passing around USB ports as if they’re vials of heroin or cocaine.”

The women were actually passing a ginger mint. They have since sued Giuliani, who recently acknowledged that his statements were false.

By early January 2021, some 60 legal challenges to the election results in battleground states, including Georgia, had failed. Yet Giuliani remained committed to blocking the presidential inauguration of Biden.

On the morning of Jan. 6, 2021, he addressed a pro-Trump rally in Washington, shortly before Trump supporters stormed the Capitol and violently disrupted the congressional certification of the election. “Let’s have trial by combat,” Giuliani exhorted the crowd.

That night — with the Capitol damaged and the nation traumatized — he continued to lobby members of Congress to block the certification of the election results, at one point leaving a voicemail message meant for Sen. Tommy Tuberville, R-Ala., with Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah.

Lee later texted Robert C. O’Brien, then the national security adviser, to say, in part: “You’ve got to listen to that message. Rudy is walking malpractice.”

By positioning himself as Trump’s spearhead, Giuliani assured himself of the relevance he craved — but at irreversible cost to his legacy as an American of consequence in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Many who served in the Trump White House blame Giuliani in part for the two impeachments of their leader. He has been suspended from practicing law in New York and Washington for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election, and an ethics panel in Washington recently recommended that he be disbarred.

“We have considered in mitigation Mr. Giuliani’s conduct following the Sept. 11 attacks as well as his prior service in the Justice Department and as Mayor of New York City,” wrote the District of Columbia Bar’s board on professional responsibility. “But all of that happened long ago.

“The misconduct here sadly transcends all his past accomplishments. It was unparalleled in its destructive purpose and effect. He sought to disrupt a presidential election and persists in his refusal to acknowledge the wrong he has done.”

Giuliani has other legal woes, among them a recent lawsuit filed by Noelle Dunphy, a former assistant, that accuses him of wage theft, sexual harassment and alcohol-fueled boorishness, saying that his sexual gratification was an “absolute requirement” of her job.

The lawsuit includes squirm-inducing audio transcripts. Through his adviser, Giuliani has said that the relationship was consensual, and he emphatically denied any wrongdoing.

Giuliani, who has intimated to friends that he is nearly broke, also faces financial challenges, rooted at least in part in his fealty to Trump, who refused to pay him for his legal work. Finally, this year, Trump’s super PAC paid $340,000 to a vendor working on Giuliani’s behalf.

Some recent career choices smack of desperation. Last year, Giuliani participated as a costumed contestant on “The Masked Singer” reality program. Dressed as a jack-in-the-box, he sang an off-key version of “Bad to the Bone.” And through the personalized video app called Cameo, he has been recording a customized video for weddings, birthdays and other events for $325.

“I can do a happy birthday greeting, or a happy anniversary greeting, or wish someone good luck on a wedding, or the birth of a child,” Giuliani says in a Cameo prototype. “We can talk about politics, we can talk about sports, or maybe motivation, or a pep talk. Sometimes people need that.”

Goodman, Giuliani’s aide-de-camp, said the former mayor and personal lawyer to a president remained the “ultimate Renaissance man and consummate all-American.” As for the many challenges before him, Goodman said it was all part of a “concerted effort by the ruling regime to send a message: Look what we can do to America’s Mayor.”

On Monday night, Giuliani bantered away on his “America’s Mayor Live” program, as the chyron below his image prophetically read “Indictment could come **ANY MINUTE** now.”

He had dressed formally for the occasion, in a dark-blue suit with the requisite American-flag pin affixed to its lapel, and was sitting at a desk in his longtime Upper East Side apartment, which he recently put on the market for $6.5 million.

For more than an hour, Giuliani described Biden as feeble and corrupt, referred to himself as “a real prosecutor,” decried plots to block another Trump presidency and urged viewers not to be down.

“We’ve got a chance to fight back,” he said. “It’s called the 2024 election.”

In the middle of the vitriol and resignation, though, Giuliani paused to promote the dietary supplements of a company that recently agreed to pay $1.1 million to settle a consumer-protection lawsuit in California over false-advertising claims.

He opened two bottles of the stuff, called Balance of Nature, and shook out a few tablets.

“I’m going to need some strength,” America’s Mayor said as he washed the pills down with water. “We have to make a trip down to Atlanta, Georgia.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Originally posted 2023-08-17 12:46:20.