The Boston Globe

State Street doubled the number of meeting spaces at its new downtown office. Sun Life added a fire pit, a prayer room, and treadmill desks. And when their new headquarters opens next year, CarGurus employees will be able to reserve their own private reclining chair to code or toggle through spreadsheets in peace for a few hours.

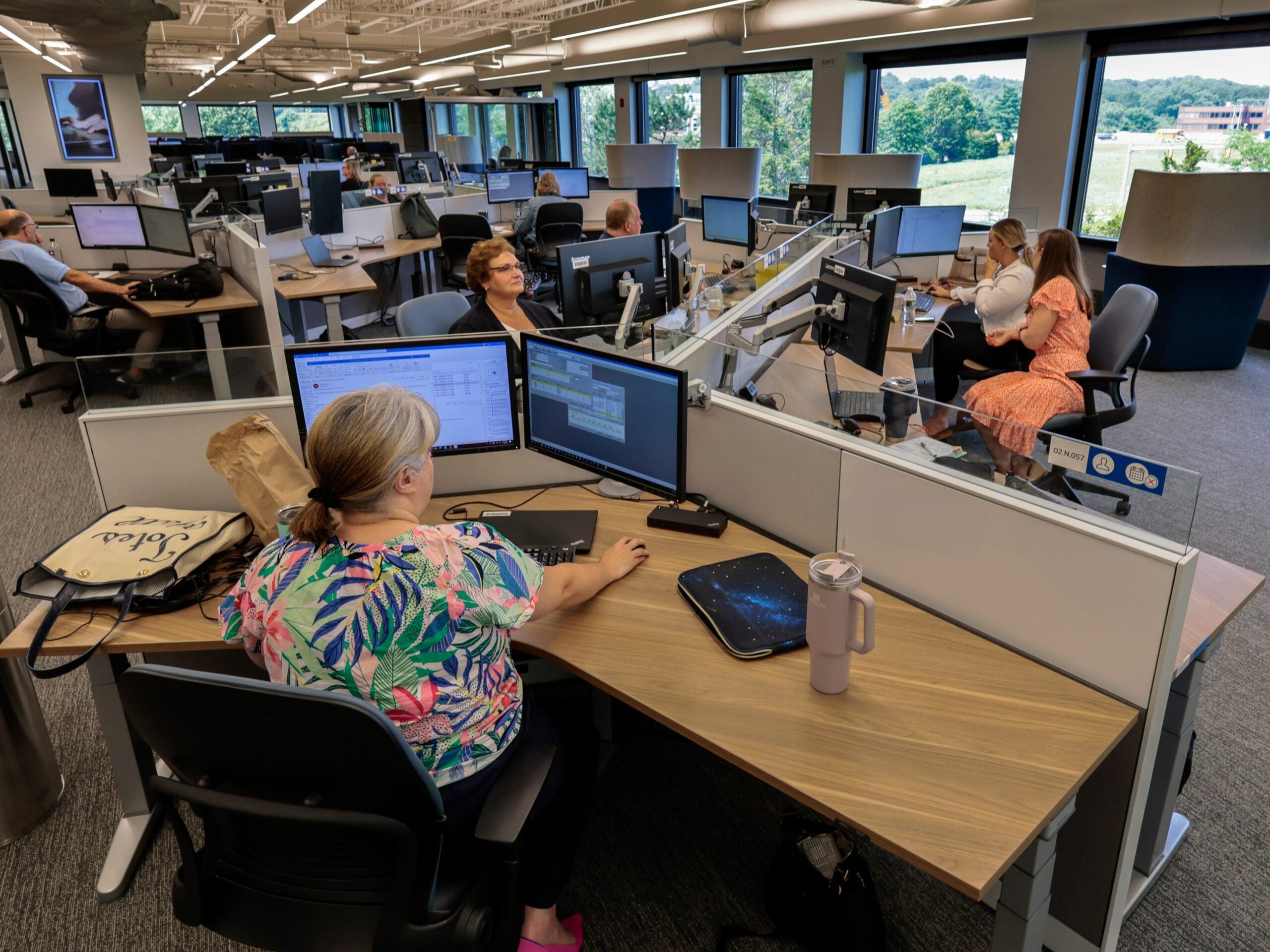

Assigned cubicles and offices are out. “Touch-down spaces,” “coffee bars,” and “neighborhoods” are in. And video screens? They’re seemingly everywhere.

The future office is here. It’s a look that has changed considerably since the COVID-19 pandemic prompted a surge in remote work, and then hybrid schedules. As a result, many Boston-area companies with leases coming up for renewal are preparing for a world where few, if any, employees trek in from home five days a week.

“When we designed this office, we were deep enough into the pandemic that we knew things were going to change, and our office design changed with it,” said SimpliSafe chief people officer Ai-Li Lim, whose company moved into a new downtown headquarters this past spring with expanded meeting spaces, more soundproof phone booths, and a modular approach that makes it easier to change layouts to meet future needs.

Office design firm Gensler keeps a running tally of popular “workplace modifications” that are increasingly being requested by clients to support hybrid work: improved collaborative environments with updated AV systems and movable furniture; more variety among workstations, to reflect how an employee’s needs might change during a workday; enhanced communal spaces such as cafés to encourage more socializing; and grouping unassigned workstations by “neighborhood” (or work team) to offer flexibility while increasing space efficiency.

Having fewer empty desks saves money for employers. But many executives say they’re plowing much of the savings into sprucing up the existing office or trading up to fancier digs. As Tom O’Brien, the developer behind State Street’s new tower at One Congress St., puts it, employers need to “earn” their workers’ commutes now.

At the same time, an increasing number of employers are prodding people to come in more frequently, to improve collaboration and bolster corporate culture. (State Street, for example, just announced it will bring back employees four days a week later this fall.) “Very few organizations want to say, ‘OK, everybody, back to five days,’” said Arlyn Vogelmann, a principal at Gensler. “But there are certain things that the organization feels like it’s lacking by not having people together.”

Insurer Sun Life U.S. undertook particularly radical changes.

President Dan Fishbein decided that the Wellesley office would no longer be the company’s headquarters. In fact, there would be no US headquarters at all. The vast majority of local employees stayed remote while Sun Life sold its campus, downsized its office space by roughly one-third, and poured tens of millions into renovating what remained. The official reopening took place in July. The redesigned 130,000-square-foot office in Wellesley can accommodate around 800 people at one time, Fishbein said, but he expects it will rarely be that crowded. (About 1,500, he said, live within commuting distance.) No one gets an assigned office or cubicle anymore. Not even the president.

“Certainly we saved some money,” Fishbein said. “But we really reinvested most of it in the space. This building was a very traditional building, and it was starting to show its age.”

Sun Life has no set requirement for showing up. The office, as Fishbein says, should be a magnet, not a mandate. A ho-hum suburban insurance office with rows of cubicles would not cut it anymore.

Sun Life tried to make it feel more like home, with kitchens and living room areas, couches and the like. Most workstations were sorted into three zones: “Library” areas, with heavily partitioned cubicles for focused work; “Collaboration” spaces, for video meetings and group work; and the “Village,” with café spaces for socializing. Fishbein said many employees will move about throughout the day. Sun Life provides handheld, lantern-shaped battery packs that workers can carry with them and plug in anywhere in and around the office.

State Street also went with a three-mode approach for One Congress: collaborative, semi-private, and private. Each team gets some enclosed offices, but it’s up to each group whether to designate those rooms for particular people or open to use by all. (Essentially only the company’s top executives have assigned offices.) State Street has doubled the amount of meeting space from its former office at One Lincoln, and those spaces feature easily moveable furniture so layouts can be reconfigured quickly. Videoconferencing screens are ubiquitous.

“The idea is that they’re not going to be going to the same desk they occupy Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday,” said Dustin Sarnoski, head of global realty at the financial services giant. “The office is mirroring the flexibility that happens with a hybrid worker.”

Assigned desks will also be gone at CarGurus when it moves to its new headquarters next year. The online auto marketplace operator will relocate from Cambridge, moving 850 employees into a new Back Bay tower with more collaboration and training spaces. There will be “focus pods,” surrounded by hexagonal partitions for privacy, as well as “lounge” pods with reclining chairs, along with traditional workstations with sit-stand desks separated by only one partition.

“We spent a ton of time and thoughtful conversation around what does the future hold, and worked backwards from there,” said Robert Mirabello, director of real estate and facilities. “If we’re able to allow employees to have choice about how they work and when they work, … they’ll have more meaningful experiences in person.”

These trends aren’t entirely new. Open floor plans and “hoteling” were growing in popularity before the pandemic hit. Now they’re even more prevalent. But companies are also working to better divide workstations to make it easier for employees to focus.

Experts at brokerage firm Avison Young say employers in this tight labor market are sculpting workplaces designed to draw employees in, rather than turn them off. That means investing in higher end touches — spaces with bigger windows and more glass interiors, for more natural light, or amenities such as coffee bars, yoga rooms, even golf simulators.

“If talent sees that these amenities are provided in one space, and not at another employer, it does impact where they choose to work,” said Michelle Osburn, head of Avison Young’s workplace consulting practice.

Not everyone is cutting back on space. Consulting giant McKinsey & Co., for example, will consolidate its Boston and Waltham operations into a new office at Winthrop Center downtown. The firm’s square footage will increase from 87,000 for the two offices to 95,000 in the new one. With teleconferencing, McKinsey consultants don’t visit client sites as frequently as they used to. As a result, McKinsey’s Boston office is getting crowded.

This will be McKinsey’s first new US office designed since the pandemic began. And as the firm doubles down on the importance of office life, it will mean some new approaches. More meeting rooms. Fewer assigned spaces. And common areas, not partner offices, get the best views.

“The one thing that Zoom has not yet managed to replace is the dynamic of two to five people being together, [working on] real-time creation,” said Alex Dichter, head of McKinsey’s Boston office. “There are tools that allow a facsimile of that through a computer. But none of them really replace being together.”